UK political parties are united around the role of forestry to address climate change

by

Rachael Levinson

Jan 08, 2020

In the UK’s general election in December, the political parties proposed very different views of the country’s future. But beyond the fractious disputes around Brexit, taxation and public spending, the parties were unusually united by one thing; the need to grow more trees. This is surely the first time since at least the 1970s that the subjects of forestry and forest industries have amounted to much more than footnotes in the manifestos of the UK’s major parties.

The new unifying factor that has brought about this sudden political enthusiasm for forestry has been climate change and the commitment of all the parties to transform the UK into a net zero carbon economy. Seemingly, the only dispute between the parties on this subject was the desired speed of the transformation.

In June 2019, the UK government passed legislation requiring the UK to reach net zero GHG emissions by 2050. The Conservative Party manifesto reaffirmed this commitment. Other parties wished to reach this goal more quickly, with the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Nationalists aiming for GHG neutrality by 2045; the Labour Party wanting “to achieve the substantial majority of [the] emissions reductions” by 2030; and the Green Party proposing even more radical policies aimed at completing the net zero transition within a decade.

All the parties recognised that if their net zero emission targets are to be reached, afforestation has a key role to play. Forests provide a host of economic, environmental and social benefits, but in the context of climate change they are especially important as sequesters of carbon from the atmosphere and providers of low-carbon materials, substitutes for emission-heavy products and fuels.

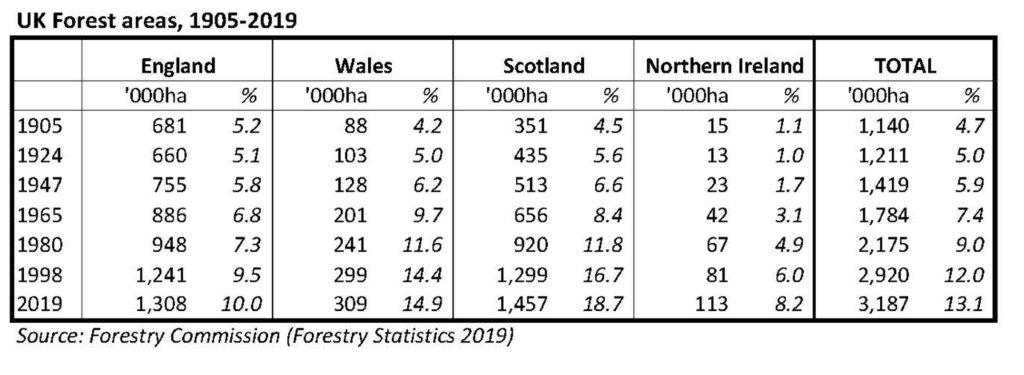

Particularly if used in conjunction with carbon capture and storage (CCS), woody biomass is seen as a vital source of low carbon (or even negative carbon) heat and power. This was emphasised by the UK’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC) which, in a report published in May 2019, set out feasible pathways towards a net zero emission goal. (See FEM #98, p10.) The CCC concluded that amongst the many measures necessary to achieve the net zero ambition is a need to increase the UK’s forested area from 13% (3.2Mha) of the total land area in 2019 to 17% (4.1Mha) in 2050, an increase of >900kha.

The CCC’s report also set out some speculative alternatives to make up for any shortfall from other GHG-saving measures, though it concluded that these could incur “very high costs or significant barriers to public acceptability”. One of the speculative measures was an even greater expansion of the UK’s forest area to 19% (4.6Mha) of the total land area in 2050.

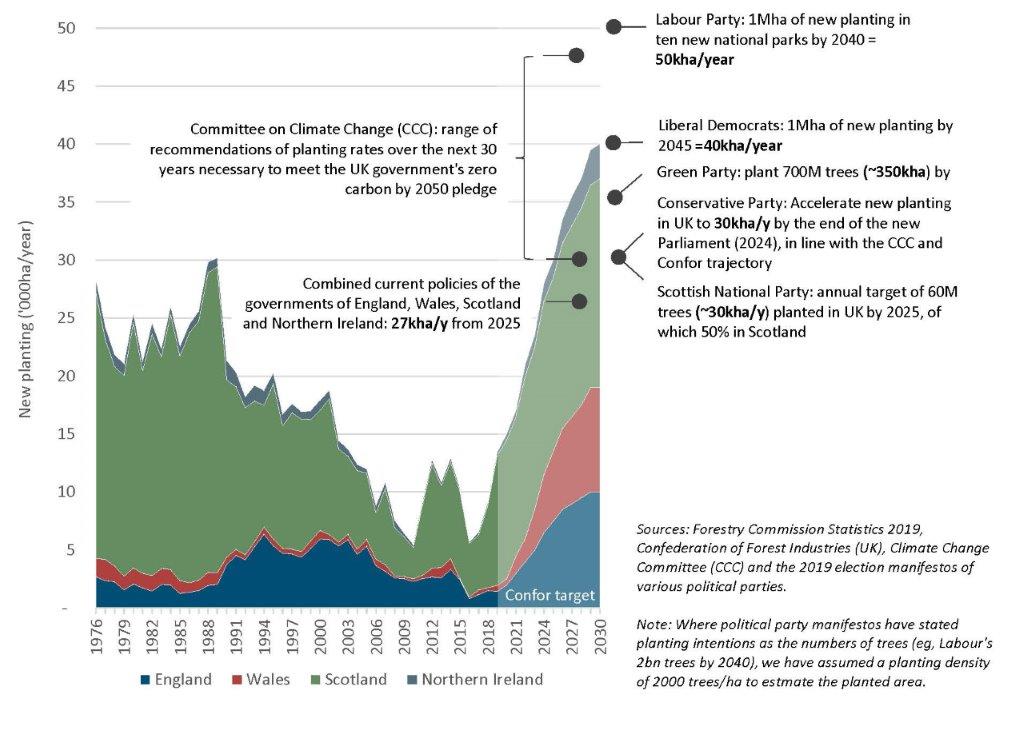

These percentages will seem quite small to audiences in North America, Central Europe, the Nordic region and in Japan where forests cover far larger proportions of the land. However, the UK is small and densely populated. Agricultural land is scarce and highly valued for crop production. Nevertheless, the UK’s forested area has been expanding for over 100 years, from 1.2Mha in the 1920s to 3.2Mha today. But new plantings have recently slowed sharply. In the 1970s and 1980s, around 20,000-25,000ha of new plantings were typical, but in the past five years annual planting has amounted to just 9,000ha/y. Of this total, just 1,500ha/y of new woodland was created in England.

Such low planting rates threaten the future of the UK’s forest industries. The new forests created 30-50 years ago – mostly of softwood species and mostly in Scotland – are now maturing and are being felled, resulting in a boom in domestic wood supply. Over the past ten years, annual softwood timber production in the UK has increased by 35%. However, given the precipitate decline in new planting, this growth cannot continue indefinitely. The latest national forest inventory report from the Forestry Commission forecasts that softwood timber availability in the UK will increase in the short-term – to 19.3Mm3 in 2027-31 from 18.1Mm3 in 2017-21 – but will then fall to 16.8Mm3 in 2023-41. Such expectations of a long term decline in domestic wood supply is hindering investment in downstream forest industries.

Confor (the UK Confederation of Forest Industries) has proposed a radical improvement in the rate of new forest planting. From the average new planting rate of just 9,000/ha/y over the past five years, Confor has set out a plan to increase the rate to 30,000 ha/y by 2025 and to 40,000 ha/y by 2030. It is encouraging to see that political parties in the general election accepted or sought to improve upon the Confor plan. (See the chart.) Most significantly, the Conservative and Scottish Nationalist parties which control forest policies in England and Scotland respectively, endorsed the new planting trajectory proposed by Confor and the CCC, at least until the end of the new parliament in 2024.

United Kingdom: New plantings 1976-2019, Confor proposals 2020-2030 and various political/policy targets to 2050

The shape of any new forest policies has not yet been made clear. Sometime this year the UK government is expected to introduce an Agriculture Bill that will replace the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) at the end of the Brexit transition period. The new bill will place greater emphasis on rewards for “work [farmers] do to enhance the environment…”. It has been suggested that this may include new incentives for woodland creation.

In the meantime, two examples of new forestry schemes are taking shape. The so-called Great Northumberland Forest in northern England expects to plant 500ha of new woodland by 2024. The Forestry Partnership that will oversee the scheme has, apparently, identified a further 120kha of land in Northumberland suitable for afforestation, though whether landowners will agree with the idea is unclear.

Also in northern England, a Northern Forest is proposed for the region that extends from Liverpool on the west coast to Hull on the east coast. Supported by local authorities and the central government it is hoped that 50M trees (~25kha) will be planted over the next 25 years. Grants of up to 85% of the planting cost are being offered.

The fact that these two relatively modest schemes have made headlines emphasizes the challenge that the UK faces if it is to reach the CCC’s goal of >900kha of new forests by 2050. Physically planting 30kha/y is not the real challenge; finding suitable land for afforestation is the greater one. For example, in the area encompassing the proposed Northern Forest, the need for 650k new homes over the next 25 years has also been identified, underlining the inevitable competition for land from urban development, infrastructure and agriculture. Much of the heavy lifting, therefore, is expected to take place in the less populated upland regions of Scotland and Wales.

The CCC’s recommended answer is an holistic one, arguing that addressing climate change requires an inevitable reallocation of scarce resources, including land. The challenge will be incentivising and appropriately rewarding a new land use policy that will enable marginal agricultural land to be converted to forestry. The new Agriculture Bill may start this process. To be successful and affordable, the new forests must have an economic purpose as well as the obvious environmental ones. Forestry expertise will need to be scaled up and foresters recruited. From this flow questions about the creation of markets for the wood that they grow. New sawmills will be needed, and housebuilders will need to be persuaded to use more timber in the homes that they build, as is common in most of Europe and North America. Growing more trees in the UK is a commendable ambition, but one that will be a multi-generational endeavour, unachievable in a single parliament.